I occasionally peruse Dell'Orto's Dungeon Fantastic; it's good stuff, and he gives me shoutouts and he's still blogging while a lot of my favorite blogs stopped, but a lot of what he discusses isn't that useful to me (and I suspect, a lot of the stuff I discuss isn't that useful to him). Part of it is our respective genres, but there's also a difference in philosophy between how he runs Felltower and how I generally run things, and I think it's typified by the paper man ethos, the amount of investment in your character that I would encourage and that he would discourage, and what that difference means for a lot of games.

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

On Paper Men and Disposable Characters

I occasionally peruse Dell'Orto's Dungeon Fantastic; it's good stuff, and he gives me shoutouts and he's still blogging while a lot of my favorite blogs stopped, but a lot of what he discusses isn't that useful to me (and I suspect, a lot of the stuff I discuss isn't that useful to him). Part of it is our respective genres, but there's also a difference in philosophy between how he runs Felltower and how I generally run things, and I think it's typified by the paper man ethos, the amount of investment in your character that I would encourage and that he would discourage, and what that difference means for a lot of games.

Monday, March 15, 2021

Musings on Scale Escalation

I'm an anime fan. It's an on-again-off-again affair: usually I'll lose interest at some point, or something else will catch my eye, and then I'll go in other directions for awhile, and then someone will recommend an anime, and before I know it, I'm buying DVDs and eating ramen, muttering that subs are better than dubs, and otherwise pretending I'm in college again.

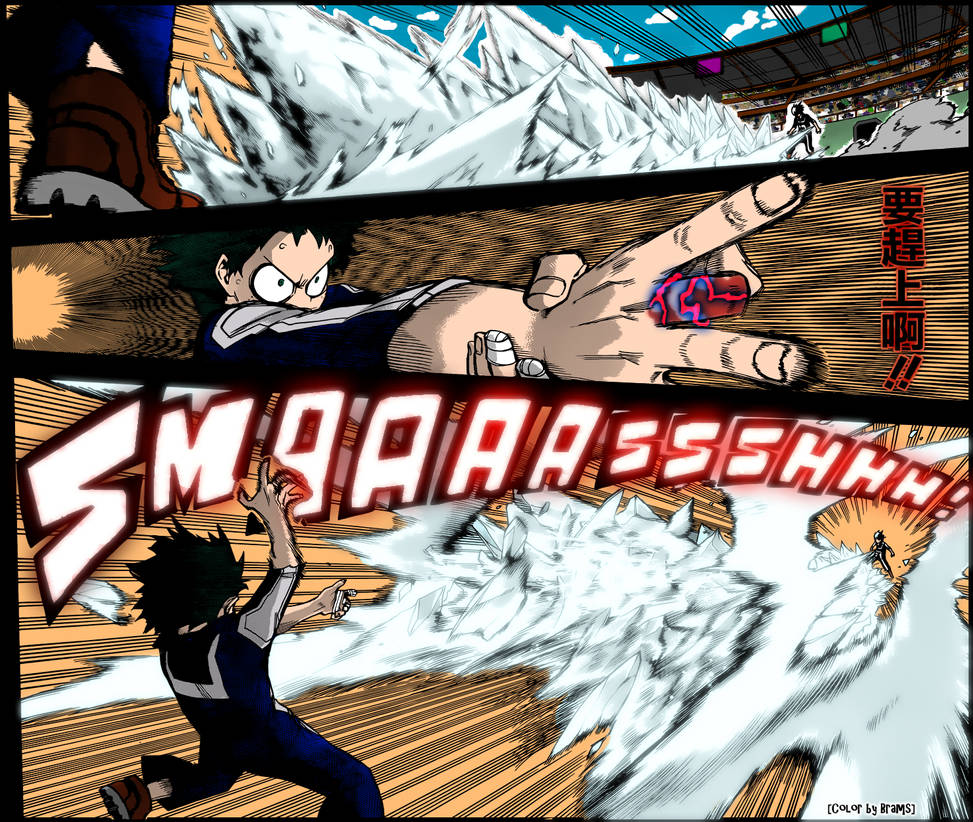

The core anime (there are a few) that has caught my interest right now is My Hero Academia, which is a very well-done, if a bit by-the-numbers, shonen anime about super-heroes. But what has struck me is how well it engages in scale escalation, though it should be noted it's hardly the only one, and in many ways, scale-mismatch is the driving tension behind One Punch Man.

Let me explain what I mean: nearly everyone in the world has super-powers, but most of the super-powers are lame: one guy might have stretchy, elastic fingers, or they might be able to light a candle. Even the cooler ones might be pretty subtle and "mystery-men esque" like they might shoot a strong tape out of their elbows, or they might be able to stick to things and that's it. But some characters have truly devastating amounts of power, like the ability to freeze an entire building solid, or create massive explosions with their hands. Most fights between supers tend to be low-scale, the sort of fights one might expect between characters on the 250-500 point level in GURPS: cool, but not mind-blowing. Like two skilled fighters could be contained in a room in a building in a city. Then suddenly a fight will erupt between higher level characters, or a high level character will unbridle their full power and the fight escalates to a new scale. You can't contain it in a small room in a single building in one city. Instead, it spills out, begins to destroy the area, or it would if it was in a city. It's no longer an "n-scale" fight, but a "d-scale" or "c-scale" where stray damage from this fight would seriously injure or kill a bystander.

We like this sort of scale escalation. It rapidly ups the stakes, and makes the fight more dynamic. The story sets the rules for us to understand. Once we have a grasp of it and the stakes, it kicks us out of that comfort zone like a mamma bird kicking the young out of its nest screaming "FLY!" The rules haven't changed so much as greatly expanded, the tensions much higher, and a few variables, which should be obvious extrapolations of the existing rules, and we watch the characters grapple with this sudden expansion. Ideally, a well-written story should make the solution to the new problem obvious in retrospect, but watching the heroes solve this new, higher-scale crisis with their smaller-scale skills drives a lot of the tension of the story.

Of course, what works in an RPG and what works in television show or movie aren't the same. Nonetheless, it's the sort of thing I've seen many a GM hunger to replicate, but it usually fails. Why?

Monday, October 5, 2020

Why your RPG Campaign is a Joke

I tend to follow GURPS blogs, which means I mostly read my own stuff and Toadkiller Dog's blog, because we seem to be the most active ones in my reading list (we've diminished a lot from the heady days of the surge of GURPS blogs back when this blog started). And, of course, reading up on Dungeon Fantasy, especially the "Rogue-like" approach he seems to favor, got me to thinking about randomness. We tend to associate that sort of gameplay with very grimdark games, but my experience is that they often lead to hilarity and a lot of jokes. Of course, most campaigns do, and I think I've made the connection between why, and why so many RPG campaigns "devolve" into comedy, and it is this:

Anytime you introduce randomness into a story, you create the opportunity for the unexpected subversion of expectations, typically in a hilarious way. Also, players need a release valve for tension.

Saturday, March 21, 2020

How to run an RPG VII: Narrative Flourishes Part II - Bisociation, Twists and Symbolism

Sunday, March 15, 2020

How to run an RPG VI: Narrative Flourishes part 1 - Alternate Narrative Structures

Saturday, February 15, 2020

How to run a Game V: The Shape of a Narrative

Or, at least, something like it. This has to do with the structure of stories, and if you're running game with a strong, narrative thread, you'll need to understand the shape and what it means. I frankly find a lot of these explanations a little terse, with a great deal of emphasis on the climax and not enough on the other parts of a story, when each part matters, especially for your sessions and campaigns. So, this post is going to dive into it in more depth, and talk about how to make that structure work for your sessions, and talk about what it all means.

Tension?

Tension as Difficulty Curve

Tension as the Fear of a Bad Ending

Tension as Complexity

Tension as Interesting Questions

- Will girl get with boy?

- Even though boy is actually a vampire?

- What about the other vampires around Boy? Will they hurt Girl?

- And her best friend is in love with him?

- Wait, shouldn't she tell her best friend that boy is a vampire? Doesn't she have a right to know? Or will she think girl is just trying to keep boy to herself?

- And she's supposed to marry Other Boy, the one that her parents are crazy about, even though he's boring and possibly a little fanatical/abusive?

- What happens if Other Boy figures out that Boy is a vampire?

- Whodunit?

- How could it be the rich heir if he was away at the time?

- But then why did he show up so quickly? And what's with his angry call?

- And why was his fiance here at the time?

- How could it be the estranged wife if she lacked the strength to do the deed?

- But does she have a lover who could make have done it? Who has she been seeing?

- And given that she was written out of the will, what would she stand to gain?

- It could have been the butler, but why?

- The butler had a good relationship with the victim

- The victim planned to add the butler to his will, but was murdered before he had a chance?

- But why does so much evidence point to the butler?

The Structure of a Story

The Introduction or "the Ordinary World."

The Inciting Incident, or "the Call to Adventure"

Rising Action or "Tests, Allies and Enemies"

The Climax or "The Descent into the Underworld" and "the Hero Triumphant"

The Denouement or "the Return to the Ordinary World"

It's Fractal!

A Worked Example

Let us return to our Ranathim Witcher-Mandalorian story suggested at the beginning. We know the basis of the story: monster hunters get hired by a death cult to rescue some sacred child that they intend to sacrifice to their dark god. We're also doing this in a linear way, so we know we want our heroes to eventually betray their clients and rescue the child and set-up a campaign long run-and-gun campaign of them vs the death cult. Thus, we need to set up a few things:- The Monster Hunter group

- The Death Cult

- The importance of the child

- A reason to betray their clients

The point of this adventure would be to give them a sense of what they do. If we expect them to do a lot of investigation, then we start them in the investigative phase of their adventure. What I wouldn't do is start them in a bar, awaiting an assignment. We'lll just start them with their assignment, because what matters isn't how they got this assignment, but that this acts as a tutorial for what it is they do: a basic investigation, kill the monster, get paid, go home.

Then we need the Call to Adventure. We'll go with full deal here, including a rejection. We can set it up like this: As they return, when they're moving through their space port, they see the sicknesses and misery that pervades Moros. They also see a Keleni woman being accosted by ruffians and assassins. She races up to them, but she doesn't beg them for help. She begs them to "save my child." She, however, can promise no payment.

This creates a choice point, and a useful one for illustrating how to route railroads to give the players a sense of choice without actually derailing the whole plot. They can choose to accept her request, in which case she explains what happens to her child and they go despite not getting paid. This doesn't actually change much about the adventure, except we don't need to worry about why they would betray the Death Cult, because they're not working for the Death Cult. However, this would violate their "get paid" clause, so they might reject her, in which case the story progresses as normal.

We might also reject it more thoroughly and begin to set up the desired betrayal in that the ruffians who have accosted her might work for the Death Cult, who are trying to prevent her from getting aid. They may seek to kill her unless someone (such as heroes) take her under their protection. If she joins up with the heroes, we might have those assassins strike at the heroes right away, and they act as the Guardians of the Threshold, or at least one Guardian. Alternatively, we can hint ominously that someone will try to kill her, and the PCs can decide if they care or not. This is a great "choice point" for a railroad adventure in that it allows the players to make a moral choice ("Do we look after the Keleni woman or not?"), one that especially rewards attentiveness ("You know, she seems afraid, maybe we should check up on her"), but doesn't derail the plot at all.

If the players reject her request, they return to their headquarters to receive the normal accolades and feasting or whatever it is we decide the Monster Hunter Guild does. We should also introduce them to a few other hunters. This isn't important now, but when they betray the Death Cult, these will turn into their enemies, so it's useful to set them up now.

Then we introduce the Death Cult and their main representative, who announces that a "sacred sacrifice" has been stolen from them. He'll refer to "the sacrifice" in neutral terms, suggesting that "it" is more of an item than a person, thus obscuring what's going on (though players who recognize the set-up will likely figure out what's going on and may well connect the child of the Keleni woman to the sacrifice. This is fine. It doesn't need to be a big reveal, and the players might at this point turn around and rejoin the Keleni woman, likely rescuing her from assassins in the process). The Death Cultists announce that they're hiring the guild to rescue the child, and the Guildmaster offers up the PCs as his best hunters. The Death Cultist seems uncertain, but then accepts them. He should be disdainful, though, and slightly insulting. Nothing sets the foundation for an eventual betrayal quite like the eventually betrayed character being a total a-hole, just be careful with how much of a jerk you make him: the point is to set the seeds to encourage a betrayal later on, not to make them ditch the mission right away.

One thing we should add here, to further help along our inevitable betrayal, is a special request that "none gaze upon the sacred offering." They're instructed to kill anyone who sees the offering. They're also given a tracker that will help them identify the sacrifice.

Let us say that the problem is that some Slavers have stolen "the sacrifice." The Death Cult High Priest (or the Keleni woman) can give them the coordinates of the planet and send them on their way. So off the players go, and then we're onto the true adventure. We can do a few things in this part:

- A space battle against a defensive, pirate patrol to get to the planet (should be minor, more explaining that the slavers have basic defenses and to allow space-based characters to have some fun)

- Fight some giant monster shortly after arriving on the world, to show how hostile and dangerous the world is, plus to reward the players for being cool in combat. This should also be a relatively easy fight.

- Find someone who can direct them to the slaver stronghold. This person might be endangered by the monster above, or help them defeat it.

- Meet rival hunters who have a different agenda (perhaps attempting to spite the Death Cultists, making them enemies right now, but possible allies in the future). These might be the pirates of the Blood Moon of Charybdis.

- Someone contracts an illness or a problem that can be endured, but will come to threaten the character eventually, but something the Child can heal (and thus earn some bennies).

Finally, they get to the fortress, which is our centerpiece. This is our climax and it should play out like a heist or a typical action scenario. The players can approach the fortress in a variety of ways: a full-frontal assault, or sneaking through the back door, or posing as slavers come to offer up their guide and/or the beautiful keleni mother to the slaver in trade for something else. The slaver boss should have some monsters or minions that pose a real challenge. Once they defeat everyone, they witness the Keleni Child, who is clearly the offering, as indicated by the tracker. The child cures the sickened PC (and you might consider giving that PC a special trait, such as a bond with the child or a unique power, to reward them for enduring such a long running penalty).

The ideal "end" of our story has the players returning to Moros with their offering, but if they go with the Keleni woman, or if they cotton on to what will inevitably happen if they bring the child back, they might just run immediately. Either way, we might see if there's some way the Death Cultists could have tracked them to this world and found their ship and be waiting for them there. We can then handle this a few ways. The cultists can just await the child to be turned over to them, and we'll see if the PCs are willing to do so. If so, the Death Cultists spring upon them "for having witnesses the child," and the PCs must fight them off and end up with the child in tow. The only way they could ruin the story at this point is to kill or abandon the child as "not worth it." Alternatively, they refuse, and the Death Cultists spring upon them for their refusal. Especially both cases, the Death Cultists brand them traitors (in the latter case, for their treachery; in the former case, for refusing to just accept death). If they joined the Keleni woman, this should be an ambush, revealing the intent of the Death Cultists to take the child and sacrifice it to their dark god. All of this sets up the coming adventure of avoiding the death cult, explaining their "treachery" to their old guild and trying to figure out the actual intentions of the Death Cult and what's so unique about the Child.

This is a basic structure, and could use some additional depth and detail, but it's runnable. It's also a good example of what a "railroad" game looks like, what sorts of choices you can offer without deviating too far off those rails.

Saturday, January 25, 2020

How to run an RPG IV: Railroads vs Sandboxes

Well, now we start diving into the deep wells of what people classically think of when running a game, and I wanted to start off by talking about the two most commons structures for a game. If you've moved around in RPG circles for awhile, you've doubtlessly heard of them and might even have opinions on which is better: "railroads" vs "sandboxes." I'm going to tell you what I think in brief, and then we'll dive into what I mean.

In short:

- Sandboxes are better than rails

- But it's not really a choice between one or the other; you'll really need to understand both and to realize that it's more of a sliding continuum.

- As a beginner, you should focus on learning and mastering rails; sandboxes will begin to come naturally to you as you become more experienced.

Saturday, January 18, 2020

How to Run a Game III: Organizing the Session

I want you to mentally set aside RPGs for a moment, and focus on a tea party, not because I'm super into tea and crumpets, but because whatever works for organizing a tea party (or a dance or a night out bowling) will work for an RPG; the only real difference is the subject matter of the event, the reason for the event, but not all the organizing around it. The reason I want you to think about this like a tea party is because I want you to be able to abstract any planning experience you have for other things and realize that it applies to planning an RPG as well.

Let's keep it simple and focus on the basics, like:

- People

- Space

- Time

- Mood

- Your purpose

Saturday, January 11, 2020

How to Run Games II: Seek Inspiration

I find that once you've realized that you have to run even a bad game and you've cleared the hurdle of your own fear of failure, the next problem is knowing what to actually do. You might accept that your first game will suck, but it doesn't help you because you don't even know what to do for your first game. So how do we get past that?

We need to cultivate inspiration. People will tell you that inspiration strikes "like a bolt from the blue," that it just happens and there's nothing you can do to make it happen. That might be true, but there are things you can do to facilitate it happening, and to take greater advantage of it when it does happen. There are also things you can do to force your gears to turn when inspiration won't strike.

Seeking Inspiration

I personally find a lot of inspiration in music, and I imagine you do too. Try to construct playlists of particular works that inspire you when thinking of a particular setting or campaign. I tend to favor more ambient, low-key music, so it doesn't distract me as I work, but it allows me to immerse myself in the "auditory world" of a particular setting, which often brings my thoughts back to the work I seek inspiration on. I also find film or video game soundtracks work great. They tend to be especially cinematic and engrossing, but aren't meant to dominate your attention the way more lyrical music is meant to.

Catching Inspiration

Forcing Inspiration

Use Creativity Tools

Brainstorm

Steal like an Artist

A Worked Psi-Wars Example

(Other ideas could work here too. The Arkhaian Spiral has Eldothic monstrosities in it, remnants of the Scourge and, of course, the Cybernetic Union, all of which could require specialists to hunt down, and these specialists might use unique "Wyrmwerks" technology. Most of these threats arose relatively recently, though, so they wouldn't have the same "ancient" feel. The Sylvan Spiral is also famous for its space monsters and genetic engineering, both of which fit the idea of a Witcher well. It tends to be more sparsely settled, though, and people tend to be more interested in visiting it than staying, so such characters might be more like guides than monster hunters, but if they were a native tradition by a group of aliens that lived in the Morass, they might act more like classic Witchers. Finally, the you might have Imperial monster hunters, some sort of corps dedicated to fighting the strange monstrosities that crop up throughout space. The Imperial Knights already verge on this. Such a unit would feel more like Black Ops than the Witcher, but that doesn't mean that Psi-Wars Black Ops is a bad campaign idea).

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

Review: Power-Ups 9: Attributes

That might seem like an odd review, but upon reading it, that was the unshakeable feeling I had. It felt like reading someone's commentary on a collection of threads about the problems with attributes. "IQ is underpriced once you buy back Per and Will," "Nobody would ever buy a 15 point talent when an attribute is so much better," "There are too many skills!" "It doesn't even make sense that Basic Speed would be attached to HT!" "I liked how HP was handled back in 3e better" and so on. In the past these sorts of things would have been addressed, typically by GURPS fans, as "Well, it makes sense because X" or "You're not allowed to buy that back because there's a hard disad limit" and other such defenses. This offers no such defenses, though it does sometimes offer the context as to why a decision was made. Instead, if anyone ever even thought of an objection to an attribute, this book attempts to address it, and other issues beside. It rips open the entire foundation beneath attributes and exposes them, sometimes more than I would have ever thought necessary.

This gave me mixed feelings about the book. On the one hand, kudos to Sean Punch. Seriously. In my experience, the RPG world is full of egotistical authors that bristle at anyone questioning their genius, while Punch says "Oh, YOU DON'T LIKE HOW WE HANDLED ATTRIBUTES? That's cool, here's why we did it, and here's 50 ideas about how you could do it differently, and some tips on how to integrate those changes into the rest of the system." Amazing. On the other hand, this claws at the thin tissue of lies that suggests GURPS is a "universal" system. If I start making changes this substantial to my game, is it GURPS anymore? Can you pick up your character from your GURPS game and come play in mine? On the other hand, could you ever? I know some people tried that, with mixed results, with D&D games, but I don't think GURPS every really pretended to be universal in the sense of total compatibility between games, just total support for all genres. In that sense, this makes it a great supplement.

I will say that unlike the other Power-Up books, this isn't something you'll reference. It reads more like a discussion, like an extended forum thread or a pyramid article, a guide on how to hack your GURPS game. Once you've gone through it, you should have a pretty good idea of what it's about, and if you're putting together a new campaign, you might revisit it once and see if it has any ideas on how to handle an attribute in your game or if you find you've run into a trait problem.

I immediately began using it in the context of Psi-Wars, and it removed the last mental block I had to lowering the cost to ST. It also generated quite some discussion as to whether we should change IQ and DX too, and this sort of underlines one of my core complaints about this book, though it's not the book's fault: a lot of what it suggests are so sweeping that if you implement them, you'll have to throw everything you've built so far out the window and start from scratch; worse, the book is persuasive, which left me feeling like I was running a sub-optimal game for running GURPS-as-written, which is probably the biggest... what's a word for an advantage that's also a disadvantage? In any case, by unflinchingly ripping open the guts to GURPS, it reveals a lot of problems you probably hadn't considered, and once it's been seen, it can't be unseen. You'll be a lot more aware of the warts of GURPS after this book. It's a book for the brave and for the game designer, not for the guy who just wants to run some campaign and doesn't care how good the rules are and he quite likes GURPS.

Saturday, January 4, 2020

How to Run a Game Part I: Experience

@Mailanka mentioned being famous for over-prep and yet always getting a feeling of stage-fright before a session in the Tall Tales channel. I'm similarly afflicted, and I think there's a dearth of good practical advice for session planning -MwnrncI sometimes talk about GM advice, but I don't go into it that much, because it's such a deep, vast topic that once I start, I will probably never stop, but if there's a lot of demand for it, and I'm working on a session anyway, I might as well spend some time talking about it.

I'll have to check that out...I've been reading Justin Alexander's blog for a while and I think his advice is generally good. But a lot of his examples sound like an attractive, charming, socially gifted person telling you that the best way to find a partner is to "just be yourself" -Mwnrnc

There's a lot of things I could talk about (a broad and deep topic) but I think the most crucial one is experience. It's also what lies beneath Mwnrnc's objection above. A lot of good GM skills can't really be picked up from reading a blog, only experienced. If you've molded yourself into a good GM, and then you're "just yourself," everything will flow fine. But then the question is "How do you mold yourself into a good GM?" and the answer to that question is one people don't particularly like: "practice."

A lot of GM skills can't be taught, only learned. Things like getting a feel for what someone wants but can't express well, or when someone isn't particularly engaged and how to get them back into the game, or how to build trust with your players so that they're willing to try out things with you that they wouldn't normally try, or just learning to be witty, so that when someone says something funny, you can instantly reply with something funnier, but that still fits in the game and keeps people engaged. If you watch a lot of the best GMs, they have this sort of charisma, this magnetic appeal. They just make games happen, and you likely have a hard time explaining, and if you ask them how they did it, they likely couldn't tell you. I personally had this experience when someone asked for help creating a session, and based on her input, I had a session spooled out in less than 15 minutes and she sort of gaped at me and asked how I can do that. I had no good answer at the time, but I do now: I simply had more experience than her.

Are good GM's just more talented than other people? Maybe. I do believe there's a darwinian force at play among GMs: bad GMs can't find players and so get winnowed out or discouraged, while good GMs have success that snowballs, so eventually, the top GMs tend to share a lot of similar traits. But I tend to be skeptical of the notion of "talent" which I think understates the amount of work it takes to become a great anything. Great artists or composers aren't born being good at these things. They work really hard at them. The same goes for being a GM.

Experience is also the best thing to focus on because, in a sense, it's the easiest advice I can give you: the way to become a great GM is to run a lot of games. If I tell you nothing else, and you follow it, you'll eventually become a great GM. Everything else is secondary, little refinements to that core advice. I can expand on that advice, and that will be the rest of the post, but the one thing to remember is that hard truth: run more games.

Monday, October 7, 2019

The Psi-Wars Fallacy

"I like Psi-Wars, but it's funny. At the beginning you talked about getting a campaign done with a minimal amount of work, and then you proceed to put years of work into it."

The comment is always given in a light-hearted "I don't mean anything by it" sort of comment, but it reads to me as an attempt by the reader to resolve a tension: either I was selling you goods at the beginning by promising that something would be easier than it was, or I was wrong and setting design is, in fact, hard.

The problem here is a misunderstanding of the underlying meaning of minimal work. I've been seeing some videos, and I got some time, so I wanted to talk about what I'm trying to show with Psi-Wars, why I do it the way I do, what I think you should be doing with your setting design and how you can avoid some major pitfalls.

Friday, April 5, 2019

The Frame vs the Game

The thing that inspired him is a comment I often make about "the game" of D&D being about "killing monsters and taking their stuff," vs other elements that other games do better. He wonders if D&D needs those elements and slides into a discussion on metanarratives and how RPGs are a sort of "controlled language," which is an interesting discussion.

But it did get me to thinking about how many people reject the label of D&D being "about killing monsters and taking their stuff." He doesn't seem to, not explicitly, but I do think about it. And while I was thinking about it, I came across an idea that I wanted to offer you to sort of show something I think is critical to understanding the bounds of RPGs, what they do, and why people often get into arguments about whether a game is "broken." It's a conversation about what the game of an RPG is, and what isn't "the game" of an RPG. It's an arbitrary distinction as you'll see, but it's useful for having a particular sort of conversation about RPGs.

Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Rant: My problem with flexible magic systems

The problem with flexible magic systems is that, despite purporting to allow unlimited flexibility in magic, they suck all the need for creativity out of a game.

(I was originally working on this when someone asked me for help on a flexible magic system so I, uh, paused it. It was also turning into something longer than I expected and I wanted to put my time on Psi-Wars, rather than a personal peeve of mine. However, this was the Patron General Topic of the Month, so I posted it; well, actually it was a tie, but this was more ready than the other topic, so this topic went up. If you'd like to vote on next month's general topic, feel free to support me via the link in the sidebar. All I ask is $1 a month).

Friday, March 1, 2019

Buckets of Technology: A Proposed Solution to Tech vs Character Points

I've been working with Ultra-Tech settings in GURPS for a long time. Some, like Psi-Wars, you've seen. A lot, like Resplendent Star Empire, G-Verse, Protocols of the Dark Engine, and Heroes of the Galactic Frontier, have only been hinted at here on this blog. Many of these lean towards heroic, even super-heroic, sci-fi and space-opera, and thus have high point totals and as a result, I've often come across a problem that anyone who has attempted to run Ultra-Tech settings with high-powered characters has: the value of technology does not match the value of character points.

Available technology, like magic or other inherent elements of the setting, are simply there for characters to pick up and use. They may require some training (represented by skill), unusual backgrounds (like Margery or High TL, if these setting elements are difficult to access), or purchase with money (if you can't just steal it or it isn't universally available), but none of these really cost much in the way of character points, rarely more than 50 for the most expensive or weirdest of things, and most often on the order of 1-5 character points, or even nothing. How much this matters depends on the tech level. A TL 3 character can start freely with a sword, while an ultra-tech character can start with a disintegrator pistol. The problem only arises when we attempt to build a character who has an inherent ability similar to the application of technology. A TL 3 character might have claws, granting him damage similar to a sword, which might cost him 5-10 points, while a character with a stare that instantly kills a target or disintegrates whatever he sees might cost him hundreds of points. Both of these are fine in the TL 3 setting (a fantasy character who can destroy you with a glance is definitely a super-heroic character), but cause problems in an ultra-tech setting: the claws are useless and the disintegrating stare, while useful, can be matched pretty easily with a purchase that a character can have with his starting budget. Why spend hundreds of points on traits like these when you can just have them "for free?"

The answer to that question is typically "Because it fits the world." Consider Marines vs Bugs, where a marine and bug are meant to be roughly on par with one another, both capable of inflicting serious harm upon the other at roughly similar scales, but one does so with technology (purchased with a modest budget) and the other innate traits (purchased with literally hundreds of points). Alien, cyborgs and psychics all feature prominently in sci-fi, but in most cases, a player would be better off investing his points in better gear and the training necessary to use that gear rather than in cybernetics, alien abilities or psychic powers. This, then, is the crux of the Tech vs CP problem, and it often stymies a lot of Ultra-Tech games.

In today's post, I'd like to briefly touch on a variety of solutions I've either used or seen proposed, and then I'll dive into my most recent solution and the one I like best: Buckets of Technology.

Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Mapping Psi-Wars 2: Galactic Map Making

I also want to comment that I'm not entirely happy with this post. Galaxies are pretty complicated, and this post was already running long, but I hope I captured the sort of core issues that one faces when going from the surface of a planet to the black sea of the stars.

Monday, January 14, 2019

Mapping Psi-Wars 1: Map-Making in Theory and Practice

Making a Map

Ever since Tolkien unveiled his Middle Earth with the luxurious map of his world therein, fantasy worlds have followed suit, and I personally find it difficult to find fantasy novels that don’t include a map. This has spilled into the fantasy RPG genre, such that Dungeon Master who begins his campaign preparations by first sketching a map has become a cliché in RPG circles. One can do a quick search of the internet to find a glut of such maps and software that can make them look fantastic.Sci-fi settings seem to have less of a close relationship with maps. Star Wars, Star Trek and Warhammer 40k all have such maps, but they don’t seem to feature nearly as prominently in the work. While sci-fi mappers certainly enjoy mapping our worlds and sectors, they seem to do so with less gusto, especially when it comes to galactic scale maps. I think this is, in part, because such maps are less visceral for readers. You intuitively understand concepts like “Mountain” and “Ocean” but “blue star” and “red star” don’t say nearly as much to you.

I’ve held off on creating a map for Psi-Wars for a variety of reasons, but my Patrons have requested it as a January topic (if you want to vote on the February topic, feel free to join us and help us build the Psi-Wars setting!), so here we are. The actual creation of a good looking map is proving quite difficult and time-consuming, so we might not see an “actual” map so much as a sketch and descriptions, but I also wanted to stop and take the time to discuss what I think the purpose of a map is, mistakes people often make, and what I’m trying to achieve with my map.

Friday, August 4, 2017

The Psi-Wars Process

| Creativity as a loop |

Up front, this is a process I've learned as a computer programmer, but I believe it applies to all creative work where possible: most artists sketch before drawing, most writers make multiple drafts and so on. But this is also informed by years of working on RPGs and struggling with the amount of work a really detailed campaign or session needs, and the amount of time I have to get work done paired with the big X factor that is the amount of learning I need to do, or the hidden complexities of my project, all of which should be familiar to any programmer. As such, I've learned a few things that have informed Psi-Wars, and my session design (as seen in the minimum viable session). The process is, at its core, this:

- Identify and articulate what it is you want to do.

- Do the minimum work necessary to achieve what the goal you want to do in step one

- Test the resulting work to see if it accomplishes the goal you set out to do

- Reflect on the work, and see what went well and see what you could Refine.

- Release the result

- Repeat until satisfied or your players bang down your door.

Thursday, June 8, 2017

GURPS Day: How are high point total campaigns possible?

So I'm just curious. How are 300+ character point campaigns even possible? I'm a "lower decks" kinda guy myself (between 100-130 points), and haven't ever considered one of those ultra-powerful types of parties. Given what I know of the GURPS 3d6 mechanics, however, how does that even work? Unless one limits the players to purchasing more breadth of Skills rather than height, it would generate Skills and Basic Attributes so high that only a 17 or 18 would indicate failure. I'd think whoever goes first in a round would pretty much accomplish every goal before anyone else had a chance, and in combat, you'd get strike/successful dodge/strike/successful dodge ad nauseam against NPCs. Unless the GM contrives clumsy penalties that mediate every dice roll. I'm sure there are supplements out there specific to high-point campaigns, and I wondered if the mechanics change somewhat in consideration of such super-powered settings. Otherwise, it would be like an AD&D campaign in which only a natural 20 or natural 1 ever indicates anything besides a miss or successful Saving Throw.

-Thomas W. ThornberryDouglas Cole, of Gaming Ballistics, spread this around the GURPS day list, and it personally struck a chord with me, not just because I so regularly run and play in these sorts of games, but because he talks my language. Breadth? Height? Bell Curves?! Let's do this!