I'm an anime fan. It's an on-again-off-again affair: usually I'll lose interest at some point, or something else will catch my eye, and then I'll go in other directions for awhile, and then someone will recommend an anime, and before I know it, I'm buying DVDs and eating ramen, muttering that subs are better than dubs, and otherwise pretending I'm in college again.

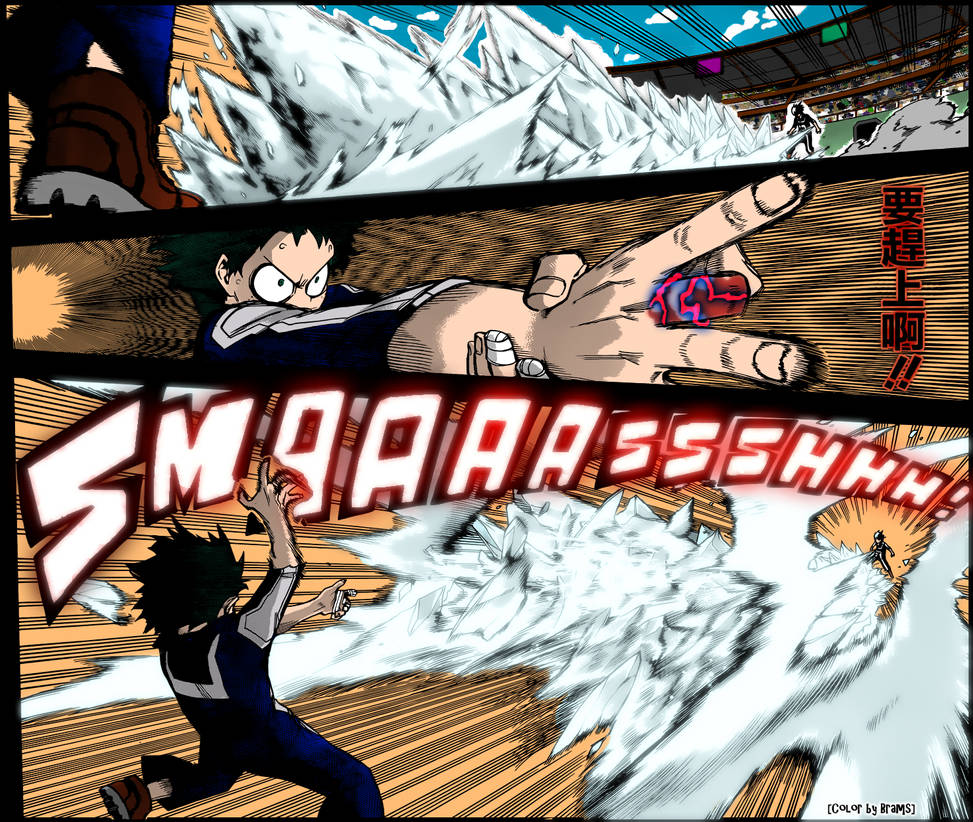

The core anime (there are a few) that has caught my interest right now is My Hero Academia, which is a very well-done, if a bit by-the-numbers,

shonen anime about super-heroes. But what has struck me is how well it engages in scale escalation, though it should be noted it's hardly the only one, and in many ways, scale-mismatch is the driving tension behind One Punch Man.

Let me explain what I mean: nearly everyone in the world has super-powers, but most of the super-powers are lame: one guy might have stretchy, elastic fingers, or they might be able to light a candle. Even the cooler ones might be pretty subtle and "mystery-men esque" like they might shoot a strong tape out of their elbows, or they might be able to stick to things and that's it. But some characters have truly devastating amounts of power, like the ability to freeze an entire building solid, or create massive explosions with their hands. Most fights between supers tend to be low-scale, the sort of fights one might expect between characters on the 250-500 point level in GURPS: cool, but not mind-blowing. Like two skilled fighters could be contained in a room in a building in a city. Then suddenly a fight will erupt between higher level characters, or a high level character will unbridle their full power and the fight escalates to a new scale. You can't contain it in a small room in a single building in one city. Instead, it spills out, begins to destroy the area, or it would if it was in a city. It's no longer an "n-scale" fight, but a "d-scale" or "c-scale" where stray damage from this fight would seriously injure or kill a bystander.

We like this sort of scale escalation. It rapidly ups the stakes, and makes the fight more dynamic. The story sets the rules for us to understand. Once we have a grasp of it and the stakes, it kicks us out of that comfort zone like a mamma bird kicking the young out of its nest screaming "FLY!" The rules haven't changed so much as greatly expanded, the tensions much higher, and a few variables, which should be obvious extrapolations of the existing rules, and we watch the characters grapple with this sudden expansion. Ideally, a well-written story should make the solution to the new problem obvious in retrospect, but watching the heroes solve this new, higher-scale crisis with their smaller-scale skills drives a lot of the tension of the story.

Of course, what works in an RPG and what works in television show or movie aren't the same. Nonetheless, it's the sort of thing I've seen many a GM hunger to replicate, but it usually fails. Why?

The Problems of Scale-Escalation in TTRPGs

(A)t the first sign of danger, any group of PCs would immediately form Voltron and have that sword pulled out. No questions asked. An inhuman shriek from above? Form Voltron, draw the sword, enter battle. The sound of an explosion from over the hill? Form Voltron, draw the sword, go investigate. Telephone rings? Form Voltron, draw the sword, answer the phone.

-- Steven Marsh, The Lessons of Voltron

That's a rather old quote. I had to dig back all the way to the year 2000 archives from Pyramid #2 to find it, and I learned that Steven really likes to talk about Voltron along the way. But it's a quote I've been thinking about a lot in regards to this problem, as it's a topic Steven touched on often in his career. The above quote highlights some of the core problems with scale-escalation, but not all of them.

A narrative can have the characters do whatever the writer needs them to. In the Voltron example, they just don't "form Voltron, pull out the sword" because it's not the right moment from the perspective of narrative tension. If they did it earlier, there would be no story, so they have to wait.

This highlights one of the core problems between a TTRPG and a narrative: because it's collaborative, one writer cannot dictate to another writer does with their character, thus everyone involved would have to agree not to "form voltron and pull out the sword" until the last moment, to not scale escalation until the narrative strictly demands it. But this would strike many people as creating artificial tension: they know they could defeat the badguy at any moment, but they're just playing their part until the last moment solely for the purpose of generating tension. But this raises the second problem with RPGs: the "authors" are also the "audience." Since you know you could just win at any moment, you're not surprised when you "form voltron, pull the sword" because you always knew that was coming and that it would win.

Of course, it must be said, that after you've seen Voltron play out this way a few times, you realize it too, and the tension there seems artificial. When the lions struggle to defeat yet another monster, you know the solution will be to "form voltron, pull the sword" so it's not particularly exciting when they do exactly that. Thus, a well-written story will create good reasons to not allow the players to escalate scale.

There is another reason scale-escalation causes problems, one you see sometimes in computer games too. Traditional RPGs generally don't involve the various authors directly collaborating to create a narrative. Instead, the authors are players, who are playing a game, and hoping that a satisfying narrative emerges from their gameplay. What we're actually seeking here is the natural emergence of that shocking scale escalation in our gameplay.

As abstractly as possible: gameplay is about manipulating a series of variables to improvise a solution that will create your desired, optimal outcome. For example, you'll apply movement to range and damage to HP to create an outcome of "Bad guys down, good guys up." Scale escalation involves wildly monkeying with those variables: suddenly, range might get huge (from fighting in a small room to ranging over a city; from fighting people who deal 1d damage against people with 10 HP to fighting people who deal 1dx10 damage against people who have 100 HP). This can easily break your scenario. Suddenly, funcational character builds cease to be functional. A bad roll can go from some mild damage to your instant death. This is, of course, part of the excitement of scale escalation. But if handled poorly, it can break the very scenario you are trying to create.

None of this means that scale-escalation can't happen in an RPG. It just means we need to make some special considerations.

Why Not Scale Escalation?

The first question we must ask is why aren't people escalating all the time? This is the riddle posed to us by the Lessons of Voltron. It's one that you can see answered in various anime adaptations of the problem. One Punch Man answers it by putting all the high scale in the hands of one character, and concocting various reasons for him to not be there, and then plays his arrival for laughs. My Hero Academia, however, has a great cornucopia of answers.

It'll hurt me: the protagonist of My Hero Academia has the ability to inflict massive, high-level damage, affect a vast area, or move at extreme speeds, but doing so destroys his body. That is, "he can only do it once." Most of the tension of the series arises from him trying to find ways around that limitation, such as resorting to "super-human flicks" at one point, because that will only destroy a single finger. If a character needs to engage in serious harm to themselves to perform the action, they'll think twice about it. This is the premise behind paying HP for powers, or for high-cost magic, like Threshold Magery.

This approach has several problems. The first is that while reluctance to use a power is the intention of the power, they might become too reluctant, and never use it, even when it is necessary. The opposite problem can occur to, as the player plays chicken with the GM. What if a Dungeon Fantasy PC has the ability to fire blast an entire room, dealing massive damage that will certainly destroy any monsters within, but he'll go unconscious for at least 15 minutes after doing so. That sounds like a desperate measure, right? But what if you walked into a dungeon room, had the PCs bolt the door behind you, fired off your blast and wiped all the monsters, then let the PCs come in, heal you up, and get you back on your feet after resting for 15 minutes. Imagine they did every room like that. Why not? What prevents them? Well, the main thing is that something might survive that blast, or a patrol will come rushing in, and find the PC at their mercy. Then they'll just kill him. So you've created a situation where either the PC wins, or the PC loses. If the PC wins, then the game ceases to be interesting because he can just cake-walk every room. If the PC loses, that's game over, so the game ceases to be interesting for him. Either way, he's pushed himself into a corner, where nothing he does will make the game fun except for articially refusing to use his nuke until the most dramatically appropriate moment, and even then, he knows it's not THAT bad, it's mostly just about ensuring that none of this blows back on him.

Limited Uses: A variation of "it'll hurt me" is that the character only has so many resources (shots, magic points, etc) that he can use before he's run out of the power. The premise is, again, that they'll refrain from using their "awesome power" until it's strictly needed, because otherwise, they risk not having it when they do need it. They don't nuke the dungeon room every time because they'll probably want it against the boss.

This still has several problems. First, as with "It'll hurt me" it can result in the character never using their power: it's so important, and so vital, that they'll try to resolve the situation without it, and if they can always resolve the situation without it (and there's good reason to design your scenarios that way), then they'll never use it. They may even realize that it's a crutch and see its use as an admission of failure (which, in a sense, it is). And if so, they may wonder why they have it at all. Alternatively, they use it right away, and spend the rest of the adventure trying to problem solve their way through, which is ultimately the same thing, but with the added downside of being anti-climactic.

You also have to be careful about what resources to spend: D&D handles this better, in my opinion, than GURPS does: magic-point systems (the default in GURPS) might price your nuke at 10 magic point, and a fireball at 1 magic point; that is, you can use one nuke or 10 fireballs. What will probably happen is that players will try to solve the problem with fireballs first, and if that doesn't work, realize they have no energy left for their nuke. D&D uses "slots" so you have one nuke slot and ten fireball slots, so you can always use 10 fireballs and one nuke, and you "use it or lose it" so they're probably going to use the nuke at some point. This cuts down on some of the problems with "limited uses."

So Rude!: It might be that the higher scale is simply inappropriate to use. For example, you might be fighting a courtly duel and drawing out a nuke is just inappropriate (it'll wreck the fine china! And your clothes!). This sort of thing requires the higher scale ability to have broad ranging consequences, which is a good idea anyway (it is not power escalation but scale escalation), and means it's inappropriate in many circumstances. It should be noted that PCs can change those circumstances, or just ignore them (If that enemy duelist really needs to die, they'll just nuke him and deal with the social fallout later). That's not necessarily the end of the world, but realize that this is a "soft" limitation at best, and one that I think most people will assume is in place anyway.

I'm not in control: It might be that the really impressive power isn't under the PC's control, but the GM's control. That is, the GM decides when you nuke, not you. This means that he picks the time, so he'll naturally choose the most dramatic moment to do so, which means the timing problems of the other two are always averted: it's always the best time.

However, this can create a deus ex machina. The wizard just ignores his nuke power until the end battle, and then suddenly, the nuke happens and the bad guy is defeated. But he didn't defeat the bad guy, the GM just announced that the PC defeated the bad guy. There's no strategy, there's no sudden revelation, he always knew it was on his sheet, and it wasn't his choice to use it, so it was cool, but it wasn't satisfying.

A slightly better way to handle this would be to allow the uncontrollable power to create a different sort of scale escalation. See, scale escalation isn't necessarily that you get a "big gun," it's also that the scale of the scenario changed. Your arena, and the rules have suddenly altered. A good example of this is a human-scale character suddenly going into a mecha-scale character: the rules and the character sheets have changed at this new scale. If your character had an uncontrollable transformation, such as turning into a large dragon or a fire-elemental which had access to nukes, but other problems (such as being big) then it feels less like a deus-ex-machina. The GM informs you that you "powered-up" but it's up to you to use this higher-scale state to actually defeat your opponent.

It also creates a situation where the PC wants on GM permission to kick ass. He learns that he can do it, but because he doesn't have control, he has to twiddle his thumbs until he gets the green light to be useful. Rather than heightening tension, this can create a situation where he just nags at the GM until he can win.

Surprise!: Finally, the GM can keep the scale escalation a secret. Rather than having a cool, uncontrollable power on their sheet, suddenly, the character is just on a higher scale. They're the wizard of destiny, and you can nuke people now, because reasons. This has the surprise value that we're looking for: when things seem hopeless, suddenly, we get a new toy to play with that lets us save the day.

While this preserves the "surprise" factor, it risks being even more of a deus ex machina. The unmagical peasant boy sword-caddy suddenly has godlike power because the story demanded it? Seems lame. In the very least, this sort of thing should be hinted at. The wizard of destiny needs to have prophecies told of him. There need to be signs of his secret, dragon-nature, or his ability to nuke. And then, when it manifests, it seems like the culmination of a prophecy, rather than the GM just solving a problem for the PCs. Otherwise, this has all the same problems as the Uncontrollable Power.

It also means the GM is dictating some aspect of a character. Maybe they didn't want to be the wizard of destiny! Or maybe they envisioned it differently! This requires working carefully with a player to make sure they get something they want, while not spoiling the inevitable surprise.

Scale-Escalating Scenario Design

The other problem is that most scenarios won't handle it, and most players don't build their characters for scale escalation. Consider: would you rather play a character that was always an expert swordsman, or was only an expert swordsman for about 5 minutes during circumstances outside of your control? There are people who will answer the affirmative to the latter, but they're rare, and they're rarely the sort of thing people think about when first creating their character. This results in counter-play by the GM: what sort of scenarios do you design? It's easier to design a scenario that challenges someone who is always an expert swordsman: if the character deals about 2d+2 damage and has a skill of 18, then your opponents need to be able to threaten someone with a parry of about 13 or so (say, some way to reliable apply a -3 penalty to their defense), and up to about 8 DR; something like 15 to 20 DR would just be too much. By contrast, if you have a character who deals about 1d+2 damage and has a skill of 14, but can blow up to 5d+2 damage and skill 25 (but probably won't), a character who is a modest threat to the weaker form, or even the expert swordsman, would get destroyed by the super-form, and a character that's a threat to the super-form would absolutely demolish the expert swordsman, never mind the base form of the super-swordsman.

This is not an insurmountable problem, of course. Part of scale escalation is carefully signalling when and where it can be expected: orcs might be balanced against a normal-scale character, but their demon-possessed boss or, even better, their God or a major Dragon, wouldn't be. Once they enter the battlefield, it should clearly signal to people to consider escalating scale if they can. It also helps to give those who can't or won't scale escalate something to do, so it's not a game of chicken. For example, if the heroes are defending a village from an orc attack, they can participate in defeating orcs, but once the dragon shows up, it becomes a natural disaster, and rescuing people from their burning homes is something that the "normal" characters can do while the "super" characters actually fight the dragon, ideally way over there, from the still marauding orcs.

You can also build standard, expected power-levels. The normal level has a predictable difficulty curve: normal characters might deal 1-3 dice of damage and have skills between 10-20. Super-scale characters might deal 5-15 damage and have skills between 20 and 30. Perhaps the super-scale characters always have certain traits, like a minimum ST of 20, or Altered Time Rate 1, or all of their attacks always hit an area of some size and scale, meaning their attacks always cause collateral damage. You might define the expected rules of the scales you want to use. You can see this as creating "gameplay" at two levels: instead of having a set of variables where the GM sometimes upends the table with wonky new numbers, you have two sets of variables, and move the players between them.

But once you've worked out your design, the players need to build to them. You need to find some way to communicate this higher level design to the players, which can sometimes spoil the surprise. In another RPG about dragons, Fireborn, players created by a human character and a dragon character, and each had their own scale. A human couldn't hope to defeat a giant, but their dragon form could. Players need the option to access these scale-escalating powers too. The GM needs to encourage them to take Secret, Uncontrollable or Limited powers that they can call upon in these higher-scale scenarios.

This collaboration between GM and player is important. A player might dump a bunch of points into secret, uncontrollable powers that the GM does nothing with, or the GM might put a lot of work into this second scale that the PCs never interface with because they never built for it ("These fights are too hard! And the other ones are too easy!")

Scale-Escalating in GURPS

I think my above musings outline some pretty solid first steps: design the "mechanics" of your game at two different levels: the "normal" scale and the "higher" scale. Then you need to give the players some way of accessing this higher tier. One option might be buckets of points, or requiring that X points be spent on these higher level elements. For example, consider treating a 250-point DF character as a "baseline" for standard gameplay, and give everyone another 50-100 points in a variety of power-ups that have limitations put on them that would allow them to "scale escalate" under certain circumstances. Offer a variety so players can choose and define for their selves. Maybe there's a "super-magic" for the wizards that has dire consequences if used, or a heightened "chi state" for the monk that can only be used for a limited amount of time, or a supernatural form that people can enter, such as turning into a dragon, or they can have phenomenonal luck or the blessing of the gods. This doesn't have to be selected at the beginning, during character creation; this could also be done later in a campaign, where they become champions of the gods, or discover secret magic items, etc. It might even be a nice quest: a grave peril threatens the kingdom, and the heroes have to go out and find some means of escalating their power, but once they get it, they don't have total control over it.

As a GM, you should maintain tight control over the constraints of these higher-scale powers. I recommend building in some innate effects that make them impractical under normal circumstances: they might inflict collateral damage, terrorize/alienate onlookers, or involve transformations that don't fit into polite spaces. Second, you should control the scale the abilities, so they fit within the bounds of the "mechanics" of your higher tier gameplay. Finally, you should make sure they are usable in some way, and that they present interesting choices and allow for "the shonen story" to naturally emerge from gameplay. I would recommend that scale escalation be at least partially under the control of the GM, but not totally. If a PC can't take his own powers out for a wildly inappropriate test run once in awhile, he'll be sorely disappointed. It's not actually a problem if a PC sometimes turns into godzilla to stomp a band of orcs, it's only a problem if he either does it all the time, or if he invalidates the ability to do so when he really needs it, or it ceases to be an interesting and dramatic reveal at the right time.

GURPS actually has plenty of tools for this. What I would recommend is a combination of Uncontrollable and Limited Uses. For example, you might be able to manifest an ability (a form, a special form of magic, etc) once (per time period), and after that, only the GM can choose to manifest it for you. It's also a good idea to slather on some negative consequences, like nuisance effects, or potential long term effects (like corruption or serious injury to the user) so that choosing to use it, or having it suddenly get used, can be really irritating, being "cursed with awesome" but in both cases, it's important that the PC has some measure of control of this: as much as possible, we want these to be the consequences of the player's choice, not the malicious caprice of the GM. Thus, the consequences should be more severe when the PC chooses to unleash something than when the GM forces it upon them.

Impulse buy points can also help. They represent a nice compromise between "hurts the character" and "limited uses" that tend to be broadly available. The PC has effectively an unlimited amount of these, but using too many can potentially cripple their character's long term growth, thus they tend not to get used unless strictly necessary. The GM could create these abilities around the idea of them costing character points to activate, but another, perhaps more interesting option, would be to limit their use or apply negative side effects, and allow impulse buys to violate these: you can manifest your dangerous power once, or you can spend CP to manifest it again and/or more safely. This allows players to strategize, and to make up for their mistakes if they fail.

Scale-Escalation in Psi-Wars

Can't go a post without talking about Psi-Wars, can I? Does it have scale-escalation? Well, in the original design, not so much. Action isn't built around scale-escalation, so it doesn't have it in its design DNA, though to be fair, most GURPS campaign frameworks don't (with the possible exception of Monster Hunters). However, as I pondered this, it occurred to me that a lot of the pieces are there.

First I've already planned for a new "tier" of Psi-Wars, higher-level play for more advanced characters. Allowing lower level characters to touch on this level occasionally is a good example of what scale-escalation might look like.

Second, Psi-Wars makes judicious use of both Impulse Buys and Extra-Effort which, in practice, allows psychics to reach astonishing degrees of power briefly, and allows them to survive extreme encounters by using the Flesh Wound rules, or buying success on improbably difficult rolls. Thus, if a "normal" character finds themselves in the wrong scale, this tends to drain their Impulse points rather than murder them.

Finally, and no doubt every Psi-Wars veteran is thinking this already, there's Communion itself. It ticks a lot of the Scale Escalation checkboxes: PCs can access it, but it's difficult, and it's ultimately under GM control and there's no limit to what it can do. Using Communion, any character with access to it can suddenly perform improbable and extremely powerful feats, even at low levels of Communion (if they get lucky and/or spend impulse buy points). Higher levels of communion only make this scale escalation more reliable.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.